All courses

Développement

Use Testing in Java to Achieve Quality Applications

To create a quality app that users love, you've got to test it properly! Discover the power of unit, integration, and end-to-end tests, use test-driven development and leverage the power of JUnit and Mockito to deliver applications that do what they're supposed to do!Medium

10 hours

Interested in this free-access course?

How do you know you're building quality software? How can you be sure that you can deliver what clients want and need? Do you want to minimize bugs, errors, and other issues that drive users and software developers crazy? Testing is the answer, and it goes beyond just checking your work - it drives software design.

The course will take you on a journey through automated testing, where you'll build and test your very own application. You'll find out why you test, how to choose tests using the testing pyramid, and write unit tests, integration tests, end-to-end tests, and acceptance tests using JUnit annotations and test-driven development!

You'll learn how to get fast feedback and sufficient coverage from your tests so you can release an application out into the world with confidence! Ready to build quality applications? Let's dive in!

Meet your teacher: Raf Gemmail

I am a proven technical leader, Agile coach, solutions architect, and full-stack polyglot with a Java engineering core. I have an outcome and a customer-centric mindset, with a history of helping both small and well-known organizations to design and deliver high-impact and data-intensive solutions.

I’ve been building software my whole life and have been fortunate enough to work with organizations such as the BBC and Booking.com. As a practitioner of London School TDD, I have led and coached many developers on their journey through making all delivery about what we have traditionally called testing. I look forward to helping you get started as well.

Write effective unit tests by using test automation best practices

Get the most out of this course

Welcome to this course on testing your Java applications. Before you dive into the content, check out some tips on how to get the most impact for your learning:

To summarize, the best way to get the most of this course is to:

Watch each video to understand why the concepts covered in each chapter matter.

Read the text below the video to learn how you can implement those concepts.

Practice along by following the step-by-step screencasts.

Test your understanding of key concepts through the end-of-part quizzes.

Get hands-on practice creating your own project through the peer-to-peer activity!

Use the testing pyramid to choose the right automated tests

What are tests?

Mistakes happen, especially when we’re “in a groove” or trying to get things out fast. Taking the time to check what we have done, especially in development, ensures that we’re sending out a quality product. It can also save us some embarrassment.

Take the case of the Ariane 5 rocket, which took rocket scientists 10 years to build 🚀...and exploded 40 seconds after launch. 😱 During the launch, a conversion error between two software programs occurred. And BOOM! 💥 Can you imagine what it felt like to be that engineer?

A little extra testing would have saved $7 billion.

I get what testing is in theory... but what does it mean when we're working with code?

Testing is how developers check that their software behaves as expected and solves the right problems. You can think of it as a team sport, where developers and everyone involved in building an application pitch in to ensure quality. But what do tests look like?

Manual tests versus automated testing

For much of the short history of software, many teams used manual testers (people) who are responsible for the quality of an application by checking running software as they use it.

Sounds pretty good to me. Isn’t that enough?

Since people can only do one thing at a time and occasionally make mistakes, manual testing is often slow and unreliable. It's also not very practical since nowadays many teams release a new version of their software several times a day.

The alternative is creating custom programs which run and check code in many different ways. We call these automated tests. Since this is code, it’s fast and can be run over and over again in seconds! There are many different types of automated tests which you can choose between, each with their own pros and cons.

Types of automated tests

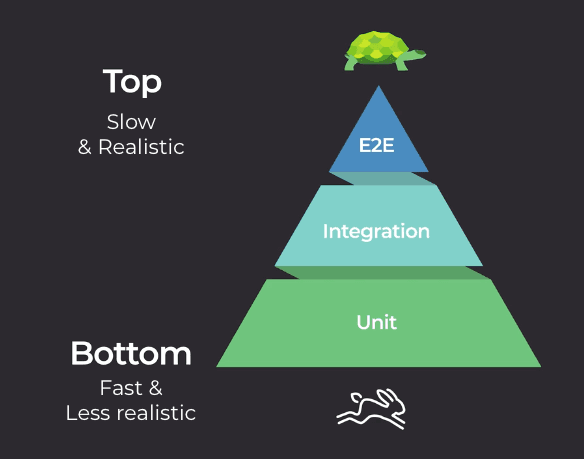

The three most common types of automated tests are unit,integration, and end-to-end, as represented in the testing pyramid below. The testing pyramid was first introduced in the early 2000s by Mike Cohn, one of the founders of the Agile movement.

As you can see, there is a higher volume of tests at the bottom of the pyramid, followed by progressively fewer as you climb to the top. The tests take longer to run as you go up the pyramid but provide more comprehensive, realistic coverage. Let’s check out the value of each one!

Unit tests

The biggest section at the base of the pyramid is unit tests that test small units of code. More specifically, they check that each individual class keeps its promises.

These are extremely quick, which means you can run a lot of them without having to sit around and wait for results. If you’ve broken something, you know about it fast and early. Since they only test individual units of code, they can’t tell you if everything in your app is working together correctly. And that’s where some of these other tests come in.

Integration tests

The next step up on the pyramid, integration tests, are slightly slower than unit tests, so you don’t write quite as many of them. Integration tests check if your units (classes) are working together as expected - assuming your unit tests are correct, of course! Since integration tests check interactions between units, you make fewer guesses about how well the final application will work. You sacrifice a little speed for realism.

End-to-end or system tests

These are the slowest tests but simulate reality more accurately. They eliminate any remaining risk by proving your application works with users in the real world (assuming your classes and their integrations are correct). For example, these tests could check whether users can switch your application on or achieve a goal. You only want a few of these tests here, as the higher up you go, the slower your tests.

Isn’t accuracy more important than speed?

The time it takes tests to run impacts their value and the cost of mistakes. Slower feedback from tests, like those from the top of the pyramid, has a real dollar value. It also means developers have to wait a lot longer to find out if they’re on the right track. That’s pretty frustrating!

For something to be checked with an end-to-end test, it has to be usable by a real user. It needs a UI or some other interface into the world. That’s where end-to-end tests run! If you were adding a new feature to your app and waited for this test, it would mean that you would have to write all the classes, integrate them with the existing ones in your app, and put a user interface in front of them. That’s a lot of work! 😅 If your test fails, some bad assumptions might have been turned into code. Fixing this will need a lot more time and work than fixing a mistake you find while unit testing!

The testing pyramid is a guideline that helps strike a balance between testing speed and code confidence. When you release software, you want to reduce the risk of introducing new bugs which break it and impact your users (or spaceships 😉). The lower this risk, the more confidence you have. By following the testing pyramid, you’ll be able to provide cleaner, faster, and overall well-tested code.

What should you test for?

Knowing about tests and tossing a few into your code isn’t enough to provide real confidence that your programs will do what they should. Let’s go back to the Ariane 5 rocket failure. Do you think they didn’t test? Of course they did! It was tested for years! But no one thought of testing that particular issue.

Test for the unexpected

Why do mistakes like that happen? When you think of a problem you want to solve with software, it’s easy to imagine a happy path. This is where the software is used just the way you’d expect, without any issues.

For example, a user might click through your app in the right order, where nothing goes wrong and ends up with a fantastic result. Or, in the case of Ariane, a rocket blasts off perfectly, or within some expected margin for error!

However, reality doesn’t always fit in with your plans. There are always going to be sad paths. When the Ariane rocket blew up, it was down to an unexpected bug which caused something bad to happen.

In fact, there will always be more sad paths than you can think of. Maybe a literature student accidentally pastes the collective works of Shakespeare into a form, or the network goes down.

But how do I make sure my application will work if I can’t think of every sad path or bug?

If you test for the more likely ones, you’ll reduce the risk of something unexpected happening, and you’ll get fewer bugs creeping in through your vents. To ensure that your software solves its target goals, your tests must check a mix of both happy and sad paths.

You can make sure they do by working with the people on your team who also care about the problem you’re solving to identify those happy and sad paths. Get together someone to think about testing, someone to think about engineering, and a product owner.

It doesn’t have to stop there though! If you still have doubts, bring in real users and other experts if you can. To make sure that everyone gets it, try and create some examples of how your application would behave in different situations. It’s easy to misunderstand small details when you work by yourself. So, talk to people!

From this, you write test cases together. Test cases just say what you would expect to see when something happens in your software. An example of this would be: “When pressing the convert button, the user should see the price in dollars.” You can then test your application by comparing what you expect with actual results.

Test to make maintenance easier

Even if you miss some important test cases, having a good amount already in place can make fixing and maintaining code a lot easier. For example, I once led a team which built a video player for a large news site. We tested our application really well, and eventually released it. Except that users soon started complaining that their mobile data was being used up when they hadn’t watched any videos. It turned out that our helpful player downloaded the videos even when they weren’t being watched. We hadn’t tested for this!

With the example above, we were able to quickly fix the video player as we had existing tests which would tell us if any of our new fixes had broken something in the existing code. This gave us the confidence to release a fix, knowing that our player would still work.

Test to communicate

There were a number of developers who worked together on this player, and they used their tests to help them communicate. Yes, tests can help you communicate!

When you’re in the middle of building software, you have a deep understanding of the code, what it’s supposed to do, and how you’d check it. You also think of new things to look for, like negative numbers or dates in the past. It’s a little like being engrossed in a book - you know the context and importance of every interaction in the story. But if you were to take a random page and give it to someone else, they’d have no idea what was going on. It’s the same thing with code. Imagine if you got transferred to a different city, and another developer had to finish writing your code. Where would they even start?

Well, your test cases will describe how people expect the software to behave. Reading your tests not only captures what your code is supposed to do but also how it works and how much of it works. If you write tests, another developer - or even ‘future you,’ if you pick up the project back up months later - will be able to understand what you were trying to do, and be confident about making changes to the code you were writing.

In other words, in a professional environment, testing is more than just a way to fix code - it’s a whole mindset. 🕶 In fact, in the next chapter, you’ll see how to integrate that mindset into how you code.

Let's recap!

The test pyramid provides a pattern to help you write tests which give you confidence in your code as you make changes.

Test automation reduces the need for manual checks and when done right, can give you the confidence to fully automate the release of your software.

Unit tests check classes quickly and thoroughly to make sure they keep their promises.

Integration tests check that the classes and parts of your application which need to work together, do so by collaborating as expected.

End-to-end tests check that users would be able to solve their problems by using your app when it’s switched on. For a web application, you’d automate this with code which pretends to be the user clicking about within the user interface.

We’ll cover each of these in more detail within the coming parts. Now you're ready to get started with your first unit test in the next chapter!

Write your first JUnit test using TDD

Where do you even start?

Now that you know a little about unit testing, let’s write one! How do we do this? Well, with complex applications, the main concern is focusing on the system under test - in other words, the thing being tested!

Um...What is a system under test? 😮

Have you ever gotten your eyes tested? You’re usually plopped into a seat with a built-in gadget and with a big chart full of letters in front of you.

The optometrist will ask you some questions, have you read the chart, check our eyes using gadgets, give you a prescription, and send you on your way. They don't switch or change the distance of the chart or install a different gadget on the chair. Everything is set up and ready so they can focus on running their test, not on how it’s done. (You're the thing being tested! 😉)

It's the same thing with unit tests. The class you’re testing is your SUT. You use testing frameworks to help focus on your SUT so that running and reporting on the automated tests is handled by the framework.

Set up your build tools and frameworks

Before we can test, we’ll need a Java project. Let’s create one!

I’m going to show you how to write JUnit tests by building a very basic calculator. We’re going to start off by creating a class which can add two numbers, and we’ll do this by writing our JUnit tests first! So let’s get started and create a new Java project. See if you can follow along!

As you saw we had to make sure that the build tool Maven knew about JUnit before we could use it as we’re introducing third-party code which our own code uses. These are called dependencies. In the screencast, when we told IntelliJ to add a Maven dependency on JUnit, it updated a special file called pom.xml. Maven uses this to decide which version of JUnit to use and make sure that we use it only for testing. You should now also be able to run your tests outside of an IDE by typing.

mvn test

Get your files in order for JUnit

To create a unit test with JUnit for a class, you’ll start by creating another class. This new one will hold all of the tests you’ll use to check your original. This is usually created under the src/test/java folder of your project, and the test class is named after the one being tested. So, you'll find all the tests for the Calculator class in CalculatorTest.

Structuring your first unit test

Now that everything is set up to test, how do you actually do it? Well, you have to set up a test within the JUnit framework:

Let's walk through each of the steps in the image one by one:

Step 1: Import JUnit annotations

To turnCalculatorTestinto a new JUnit test, start by importing JUnit’s@Testannotation with the following code:import org.junit.*;.

Step 2: Place

@Testin front of a method

To create a test with JUnit, make a new class and add the@Testannotation above each method which performs your test.Step 3: Write a descriptive name

The method name should clearly describe what is being tested. It’s important to give your tests a name which describes what the test is checking for.

How do you actually structure the content of your tests? To write reliable tests, it makes sense to follow the popular acronym, AAA. (This has nothing to do with automobiles. 😉) It stands for arrange, act, and assert. The goal of this structure is to keep tests independent and avoid interfering with one another. And guess what? We're going to act, arrange, and assert as our next steps:

Let's go through each of the steps in the image above:

Step 4: Arrange - Set up the class under test

Arrange is another way of saying set up. When you write a unit test for a class, you start by setting up an instance of the class you are going to test. Do this by callingnewon it. This is called your class under test(CUT), or in other words, the thing you’re testing!Step 5: Act - Call the method you’re testing

Now that you’ve got your test arranged, you’ll act on this. Basically, you prod at it with your testing wand by calling its methods. The methods should do something which you can check for, or return a result.Step 6: Assert - Check the result with an assertion

Now that you know what you’re checking, you assert your expectations. You want to compare an expected value with the actual value returned by the method you’re testing. If they match, your test passes. If they don’t, you fix it so they pass. You do this by adding an assertion!

An assertion is a statement which calls out what you think should happen in your test. If an assertion does not turn out to be correct when the test runs, then it fails. It also fails the whole JUnit test. It's best to have only one assertion per test. This way, you immediately know which assertion is failing and can focus on fixing one thing at a time.

Now, that you know what the steps are, let's take a closer look at that image again:

In the image above, the result of calculatorUnderTest.add(1,1) is compared with the number 2 using assertEquals. Here, you’re testing the assertion that two values are equal. This is just one of the assertions JUnit makes available when you import org.junit (like in Step 1). assertEquals simply tests that the returned value from calculatorUnderTest.add(1,1) is the same as the value you expected to get back.

Okay, it's set up! But how do I run it?

Whether you’re using IntelliJ or Eclipse, you can now right-click on the test name and select Run. The above example was run using IntelliJ. Have a look at the green tick. Can you tell what it’s testing? 😎 Adding two positive numbers correctly! And it looks like the test has passed. ✅

Had the assertion failed because the add method was buggy, you would have seen something like:

You can see that the test failed (It has a round cross beside it) as the Actual (0 in this case) didn’t match the Expected value (2).

Using TDD: red-green-refactor!

You might have noticed that we started writing tests before anything else in the code. This follows a technique called test-driven development, or TDD. Using this technique means the code you build remains focused on passing those tests. Did you notice how writing the test before the code allowed us to describe what the add method would look like? From there, we just had to allow our IDE to create it for us. 🙃

Okay, I get the gist from what we did, but how exactly does this work?

Kent Beck, the creator of TDD, introduced many developers to the following pattern:

In this pattern, you loop through the following steps:

Write a failing unit test. 🔴

Write the code to make the test pass. ✅

Clean up the code without failing the tests. 🔶

Write the next test and repeat! 🔄

This is called red-green-refactor. Failed tests are described as red. Much like a traffic signal, red tells you to stop and make your code work.🚦When they pass, they are green. Green tells you to go and refactor. This simply means that you can try and make your code more readable or elegant without changing the way it behaves.

Because the test is already in place, it lets you know right away if you break any behavior, ensuring that you’re always focused on functionality first.

It turns out that if you write your code after your test, that code is easier to test. That’s because it’s made to be tested! Testable code is usually clearer code. Remember, try and keep your tests focused on one thing. As you write a focused test for each class, TDD encourages you to build software out of lots of little classes, each doing one thing well. This adds to the clarity of the code. It’s easier to follow one thing than 50. 😛

As you test software, you also learn about the code you need to build to pass those tests. This also shapes a minimal and modular design, meaning that your code isn’t clumped together in a few classes. Modular code is flexible and very easy to change. Why should you care if it’s easy to change? Any software you build at work will last for many years and continuously change as your users’ needs also change. This keeps you in a job! TDD makes the job easier. 😎

Try it out for yourself!

Have a go at adding a Calculator.multiply method! Remember to write your test first and make it go red before you write the code! You can clone the repository and add your own code to it!

git clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJava.git git checkout p1-c3-sc-1-to-3

Or use your IDE to clone the repository and check out the branch p1-c3-sc-1-to-3. You can now explore the examples from the screencast and try running the tests with mvn test.

Let's recap!

JUnit is a testing framework which helps you focus on validating classes.

To use JUnit, you need to add a testing dependency to your build tool.

Build software using red-green-refactor where you:

Start with red failing tests which describe what you plan to build.

Make the tests pass and go green by building the code in the most direct way.

Improve the readability of your code by refactoring it without breaking the test.

Now that you've got the basics down, let's make our tests more understandable in the next chapter!

Use TDD and Hamcrest to write easy to read code

Imagine you have a group of friends coming over, and you decide to order pizza. Before you proceed with the order, you might ask yourself: How many people want a pizza? What type of pizza do they want? Does anyone have special requirements, such as vegan or no tomatoes? How do you know which pizzas to get? Keep in mind, it might take half an hour for your pizza to get there. You’re all starving, so you don’t want to have to send it back and wait even longer. What do you do?

You could play it safe and buy more than you think you need, but you’ll spend way more money, have to wait longer for the pizzas to be prepared, and risk your friends not liking what you ordered. The longer you wait to find out you’ve ordered the wrong pizzas, the hangrier everyone will get. 😩 If you ask your friends what they’d like, there might be some upfront squabbling, but at least you won’t have to send any pizzas back.

Software is the same. There’s nothing so soul destroying as investing days in writing software which ends up needing to be re-written because it didn’t do the right thing. In other words, ordering the wrong pizza. 🍕The users of your software also lose out as they have to wait for even longer for their feature. How do you avoid these issues?

Use TDD to avoid the costs of misunderstandings

Test-driven development (TDD) helps you avoid this. As you saw in the last chapter, with TDD, you create a new automated test before writing your code. To avoid confusion about what the software should be doing, it is important that your tests clearly explain what they are testing. This keeps your focus on solving one problem at a time and helps others on your team understand what are trying to achieve!

Why should I do it that way?

Lots of studies have shown that it is hundreds of times more expensive to fix a bug, the later it is found.

Using TDD to communicate what you’re testing, catches bugs while you are still coding. Sometimes before you even turn on your PC. TDD can save you from coding the wrong thing, or misunderstanding a test case.

This makes sense, right? If you find out that your code is wrong as you’re writing it, you can fix it immediately. TDD helps you to do this by making your test cases readable to others and starting you off with the confidence that your code does what it’s supposed to! If it takes a year to find out that your application has mistakes, you might have to go on a bug hunt through the whole codebase! This will take much longer!

How can I make my tests meaningful enough to help avoid mistakes? This is code, right?

Writing easy to read tests with Hamcrest

Did you notice how the test in the previous chapter used JUnit’s assertEquals? Would you ever say "assert equals" in everyday life? Ever?

You: "Can I assertEquals that you're in good health?”

Your friend: ... 🤷🏻♀️

Would you assertEquals that the way we're talking is very robotic? Hey, people don’t talk like that! So why should your tests?

You want the tests to express what your software should be doing! Tests are tools for communicating with yourself in the future, as well as with others. If you understand how it should behave, then you know if it works!

You might be thinking that this is just code though. How are you supposed to get any clearer in an artificial language? There is a popular library called Hamcrest, which many Java projects use to make their test assertions a little more natural to read than JUnit’s assertions. It is designed so that your code flows naturally, and more closely resembles spoken language.

You can see the difference between Hamcrest and JUnit’s assertTrue in this example. assertTrue will only pass if the value you pass it is true. Let’s compare it with Hamcrest’s more expressive language:

Test case: A name is between 5 and 10 characters long. | ||

JUnit Assertions | Hamcrest | |

IN CODE |

|

|

READ ALOUD | “assertTrue name length greater than four and name length less than 11” | “assert that name length is greater than 4 and is less than 11” |

While JUnit assertions might look shorter, Hamcrest’s (aka matchers) read more naturally. You can describe simple and complex tests by putting them together in different orders, like the words you use every day. Having a rich vocabulary helps you express your ideas clearly. TDD is like thinking out loud when using matchers.

Let’s use Hamcrest to do some TDD!

Are you ready to have a go at using Hamcrest? Remember that test from the last chapter? Our calculator’s add method was tested with an assertEquals comparing two values. Let’s now add multiplication to the calculator:

Try reading this aloud. 🙄 Fortunately, Hamcrest has got our back here!

</p>

You’ll get Hamcrest’s most important matchers for free as they are included with JUnit 4. They just come together. If you use JUnit5, you’ll have to add a dependency for it as it’s no longer built into JUnit. Most projects still use JUnit 4 though.

Did you see the way we added more expressivity by combining the is matcher with the equalTo matcher? In the previous example, we also put an and matcher with isGreaterThan and isLessThan matchers. Hamcrest helps you express what it is that you intend to test. This helps to keep you focused.

Let’s be honest. The language is still a little robotic, right? You can’t get away from this since Java is a programming language. The important thing is that you have a language which flows and can be used to describe your intent a little more naturally.

Let me give you some other examples. Imagine I had a set of animals and wanted to test that it contained cats and dogs.

I write: assertThat(animalSet, hasItems(“cat”, “dog”)) or assertThat(animalSet, contains(“cat”,“dog”).

How natural it sounds is down to the matchers you use. These are just two of the many matchers provided by Hamcrest. They come in all shapes and sizes with lots of different vocabulary. Some of the more useful ones are:

Matcher | Example | What happens when your test fails? |

is() - Compares two values | assertThat(“a kitten”, is(“a kitten”) assertThat(“a kitten”, is( equalTo(“a kitten”)) | Expected: is "a dog" but: was "a kitten" |

equalTo() | assertThat(“a kitten”, equalTo(“a kitten”)) | Expected: "a dog" but: was "a kitten" |

not() | assertThat(“a kitten”, is( not( “a dog”) ) | Expected: is not "a kitten" but: was "a kitten" |

both(..).and(..) | assertThat(“a kitten”, both(is(“a kitten”).and(endsWith(“n”)) | Expected: (is "a kitten" and a string ending with "dog") but: a string ending with "dog" was "a kitten" |

Let's recap!

Test-driven development keeps your focus on solving one problem at a time.

By describing tests using clear language, you can catch any misunderstandings early.

The later you catch a defect or misunderstanding in your code, the more it will cost to correct.

Hamcrest matchers provides more readable assertions. You can put these together in different ways to clearly express what you are testing for.

Proper naming helps make our code easy to read and understand, but so do annotations! Intrigued? Find out more in the next chapter!

Create more powerful tests using JUnit annotations

“No cameras!” 📸 Has anyone ever said this to you?

Have you ever gone into off-limits areas at a museum? 🚫 Have you taken a picture where it wasn’t permitted? How did you avoid parking in the chief curator’s parking slot? Signs, right?

Signs can save you a lot of trouble by helping you do the right thing. Java also gives special signs called annotations which help you tell your code how it should behave. They start with an @ and each has its own special meaning.

You’ve already seen one! @Test is a JUnit 4 annotation which can be put before a method. With @Test, JUnit will immediately know that of all the methods in that file, this one is supposed to be run as a test. It will take the name of the method and make it the name of the test.

There are many useful annotations which come with JUnit, and I’ll introduce some of these to you. They can help make your tests super powerful and save you lines of code! To use these annotations, drop them into your test class, a little like putting up a new sign in a museum.

Let’s annotate!

I bet you’re dying to see JUnit’s annotations in action! Let’s dig in!

We’re going to add a few annotations to our CalculatorTest. The test class should be named after the class under test (CUT). Since we’re testing a calculator, let’s walk through a CalculatorTest which uses the basic annotations of: @BeforeClass, @AfterClass, @Before, @After, and some special spins on the @Test annotations:

public class CalculatorTest {

private static Instant startedAt;

private Calculator calculatorUnderTest; We have added a static variable and class field to use in the example above. Now, let's check out @BeforeClass:

@BeforeClass

public static void beforeClass() {

//let's capture the time when the test was run

System.out.println("Before class");

statedAt = Instant.now();

}@BeforeClass will cause a method to run once before our first test. In this example, we store the time when the tests were loaded. Next is @AfterClass:

@AfterClass

public static void afterClass() {

// Not the way to do it. Just illusrating @AfterClass

// How long did the tests take?

Instant endedAt = Instand.now();

Duration duration = Duration.between(startedAt, endedAt);

System.out.println("Tests took" + duration.toString());

}@AfterClass marks a method to be run once after our last test has completed. This will run even if the tests fail. Here we measure how long it took to run the tests.

Next is @Before:

@Before

public void setUp() {

// Recreate the calculator before each test

calculatorUnderTest = new Calculator();

System.out.println("Before Test:" + Instant.now());

}@Before marks a method so it can be run before each @Test. Here we make sure that we’ve created a new instance of Calculator.

Now we've got @After:

@After

public void tearDown() {

// set calculator to null after each test

calculatorUnderTest = null;

System.out.println("After Test" + Instant.now());

}@After marks a method to be run as soon as JUnit has finished running a @Test. This is often used to clean up things done in @Before. You’ve already seen the @Test annotation. Let’s look at some options to make testing even simpler:

As you saw, the assertion to test for an exception can be passed directly to @Test. Use the expected argument as well as the value of the exception class you expect to see being thrown.

@Test(expected=Exception.class)

public void add_returnsTheSum_ofTwoPositiveNumbers() throws Exception {

Double expected = 3.0;

Double sum = calculatorUnderTest.add(left:1.0, right:2.0);

assertThat(expected,is (equalTo(sum)));

//prentend this was from your code!

throw new Exception ("We expect an Exception");

}@Test(expected=<Exception.class> ) passes some options to @Test which allow you to test sad paths where you expect a particular exception to be thrown.

Let’s look at how tests can let you know if the methods they are testing suddenly become too slow:

As you saw, you can pass @Test the timeout argument with a value of the time, in milliseconds, which the test should not exceed. That way, your tests will tell you if you ever put a slow algorithm into your code!

@Test(timeout=1000)

public void add_returnsTheSum_OfTwoNegativeNumbers() throws Exception {

Double expected = -3.0;

Double sum = calculatorUnderTest.add(left:-1.0, right:-2.0);

assertThat(expected, is(equalTo(sum)));

// Let's timeout our test

Thread.sleep(millis:2000);

}@Test(timeout=1000) fails the test marked with this annotation if it takes longer than 1000ms (1 second). Can you see that the test is rigged to fail?

This is what happens when you run it:

Try and match up the printed messages (e.g., before class in the right panel) with the steps in the code above. Can you see which test failed?

It's your turn now!

Check out the repository and try running these tests for yourself.

git clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJava.git git checkout p1-c5-sc2-to-sc3

Or, use your IDE to clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJava.git and check out the branch p1-c5-sc2-to-sc3.

You can now explore the examples from the screencast and try running the tests with:

mvn test

Let's recap!

JUnit’s annotations help you write clearer tests without unnecessary repetition.

Some common annotations are:

Annotation | When to use it |

| If testing method which should not be too slow, you can force it to fail the test. |

| Use this annotation to test if your class throws an exception. Don’t use try/catch to test for it. |

| Run a method prior to each test. This is a great place to set up or to arrange a precondition for your tests. |

| Run a method after each test. This is a great place to clean up or satisfy some post-condition. |

| Mark a static method so it runs before all your tests. You can use this to set up other static variables for your tests. |

| Mark a static method as being run after all your tests. You can use this to clean up static dependencies. |

Now that you know how to do unit testing, let's make it even easier by adding some effective plugins...in the next chapter! See you there!

Improve code confidence with build tools and test report plugins

Even with all this testing, how can you be sure you’re building quality software?

You do TDD, right?

Nice! Can you think of anything else you’d want to be sure of before claiming to have written high-quality code?

How about that other developers don’t have trouble reading your code? Or that you haven’t let a bug creep in between your tests? What about being sure that you haven’t chosen to use a dependency with known security issues? Do you want to be sure that you’ve tested enough to be true to the testing pyramid?

I’m sure that you answered "yes" to all of these questions. 😉 Fortunately, Java has been around for a while and has a bunch of tools that let you automate solutions for these issues. You can run automatic checks as part of the build. This goes beyond just automating your tests: you can add checks on the quality of your code and your tests!

With each small change you push out, the software then gets built automatically in a continuous integration environment, and checked!

This environment is usually, in some form or another, another computer dedicated to proving that all the tests and quality checks pass somewhere other than on local desktops (3). When things don’t work out, it helps to have reports to look at (5) - and we'll show you a few good tools for doing that in the sections below. You can use these to communicate with other experts and make your whole team aware of what has broken. We’re all responsible for the quality, right?

If things don’t work out, it is called breaking the build. A crime punishable by having to buy doughnuts! 🍩 Remember that you’re always working in a shared codebase, so breaking something in your codebase, breaks it for everyone. You should only release your code into the world when everything runs without breaking the build (6).

So, ready to check out some build tools and report generating tools? Or do you really want to be the one bringing in doughnuts to the office? 😉

Build tools

When you create a new class in Java, you’re just editing a regular text file with a .java at the end, and writing inside. IDEs are very good at telling you if there’s anything wrong with your use of the Java language, but they don’t really run that .java file. Java is a compiled language and needs the JDK‘s compiler to build the .java files into .class files, with instructions the JVM can efficiently run. In other words, since the build is done on your computer, you can only be sure that it works on your computer.

How can I be sure that it can be built by any other developer on my team? Or on any other computer?

You use build tools like Maven or Gradle that let you list which dependencies your code needs (E.g., JUnit v4 or Spring v5). It then compiles your code and runs your tests. Finally, it can package .class files so your working app can get shipped.

Any developer with access to your project and the same build tools can then build, test, and package your code. So the build tool runs your unit, integration, and E2E tests for you! 😀Wouldn’t it be great if it also ran those other quality checks we talked about? Stuff to make sure that your tests and code are well written? You guessed it. Both Maven and Gradle can do this, via some seriously cool plugins.

Configuring Maven can be an art in itself and there is a lot of fine documentation out there; however, that shouldn't stop you having a look at a project and some of the plugins you can use to report on the overall quality of your software.

Let's check it out:

It gets even better. Many of these tools come with useful reports and dashboards. This helps your whole team measure and understand the overall quality of your software. Many of my teams have even had large screens in our work area, displaying the health of our build.

Let's continue with that example code and see what the reports look like and where they live:

As you saw, we used a range of plugins to create a variety of reports. Let's look at them and why they are useful.

Surefire

If you’re using Gradle, just running Gradle test is enough to generate an HTML report. With Maven, you use the Surefire plugin to report on your tests and make an HTML report. This is great because you could put it on display for your whole team, and if something breaks, everyone will know about it!

Maven creates an XML report when your tests fail, but can be made to create an HTML report when you run:

mvn site

Maven places your reports in the target/site/surefire-report.html. It’s not the most stylish thing, but tells you how your tests did. See if you can figure out what failed:

Checkstyle

When you have lint on a jacket, you might use some tape to remove unwanted fibers which stand out. Checkstyle is a Java linting tool, which means that it looks at your source code and points out undesirable coding styles which stand out.

Who gets to pick what is desirable though? 🤔

It's a common practice for teams to have coding standards. This ensures that the code is consistent regarding important things like tabs versus spaces. This may seem silly, but without it, developers will spend half their time fighting their IDEs, and your code.

Checkstyle goes beyond tabs and spaces. It is highly customizable, and enforces styles of variable naming, class naming, indentation, bracketing, and much more. There are many preset configurations. You can even start by using the Java styles of Google and Oracle.

It’s also great at picking out gotchas. Take the following example on the left:

|

|

It looks harmless to follow your if by the thing it should execute when userValid is true. But imagine what would happen if I decided to log the transfer right before transferring the money? You can see that it might be easy to forget the brackets. This would call transferMoney even if the user wasn’t valid!

Not using {brackets} after an if is considered an anti-pattern. That is a bad habit you should avoid, as the long-term consequence can be unhealthy. You won’t contract an illness, but we’ve learned over time that certain anti-patterns can make your code unmaintainable.

To give you a feel for the many checks it can do, let’s talk about one of the more amusingly named ones. Cyclomatic complexity. Obviously, you know what this is, right?

...😰

I’m kidding. I remember once thinking that it was a reference to a washing machine feature. 😉

Cyclomatic complexity is a metric for measuring how many nested conditions (or ifs) your code has. Why is this important? The more nested “if.. then.. if.. then.. if..” type statements you have, the more paths you have to test. The number of combinations grows rapidly. So, a higher cyclomatic complexity points to a higher probability of bugs. Essentially, it is the number of possible paths the JVM could take through the lines of your code.

Checkstyle helps reduce the number of defects you produce. It does this by reporting on overly complex code and known bad practices, as you’re building it. Maven has a plugin you can use to add it to your build tool. You can even configure it to fail your build if the code isn’t good enough.

Start by running:

mvn checkstyle:checkstyle-aggregate

This produces a report, which is not particularly attractive. When you scroll to the bottom, you can see how your classes violated good practices:

It’s a bit hard to read at first, but the report also contains a link which teaches you about each type of violation. So in the case of FinalParameters, you can click through to documentation which will teach you that it’s safer to change add(Double left, Double right) to add(final Double left, final Double right) and why.

Jacoco

Another popular plugin for Java build tools is Jacoco. How do you know if you’ve tested enough? We talked about the many paths through your code when you have nested if statements. Every line of code used has the potential to go wrong.

Jacoco allows you to run your tests and check how much of your whole codebase was visited by your tests.

It’s a little like strapping a GPS to your back and then sending you out into a big city to go for a stroll. If I sent you for a walk through Paris and then measured the percentage of streets you walked, it probably wouldn’t be very many because it's a huge city. I’d need a few teams of testers to walk the main streets if I’m to get coverage.

There are three lessons in this little anecdote:

It’s hard to get confidence on a large software project, so try and keep your projects small and good at doing one thing.

Keep your code simple, and write lots of unit tests to target your complex classes.

Don’t let me strap a GPS on your back! 😎

Jacoco also has a handy plugin which you can integrate into your build.

When an HTML report is generated with mvn site, you can see target/site/jacoco has been created with HTML files. If you look at these, you’d see a summary showing the percentage of tested methods per class. You can drill even deeper to see something like the following:

Can you see that the subtract() method in this example doesn’t have any tests? It’s all red. This can help you write tests where you’ve forgotten to.

Can you see that the subtract() method in this example doesn’t have any tests? It’s all red. This can help you write tests where you’ve forgotten to.

FindBugs

FindBugs is another gem of a tool, which analyzes your Java code and helps you improve its quality. FindBugs is a little like Checkstyle, in that it performs static analysis of your source code to look for things you shouldn’t be doing.

Static analysis examines what your Java code looks like, and finds patterns so it can make a judgment about possible risks. This is a little like taking an online survey to check your health, but more reliable. FindBugs has a huge database of different types of known software bugs. It finds code doing things which were probably not intended, doesn’t follow good practices, and may introduce a security risk.

FindBugs has a plugin which you can integrate with your build tools. You can check for bugs with mvn findbugs:findbugs, or generate an HTML report with mvn site. Imagine that you had this buggy code which calls a method on null reference:

public Double subtract(final Double left, final Double right) {

// What does findbugs think of this impossible situation?

if (left==null && left.isNaN())

System.out.println("Do not run this line of code");

}FindBugs would report this as:

Okay, it’s a little vague, but if you click through the NP_ALWAYS_NULL, it will explain it:

As left is null, and left.isNan() gets called, this will blow up with a NullPointerException.

Other plugins

All of these plugins perform static analysis of your code and help you measure its quality. There are many more great plugins out there. If you’re interested, you can check out OWASP Dependency Checker, a security vulnerability scanner. OWASP provides great resources and guidance on building secure applications; it would be well worth checking out OpenClassrooms’ OWASP course!

There’s more. You should also check out PMD, another bug finder similar to FindBugs. My top tip would be to look at SonarQube, which does all the things we’ve seen here but in one very visual place. It does involve a little more setting up, though.

Try it out for yourself!

Clone the repository below, and run Maven commands in its README.md. See if you can fix some of the issues!

git clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJavaB

Or use your IDE to clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJavaB

You can now explore the examples from the screencast and try running the tests with:

mvn clean test site

Remember to have a look at the README. 😉

Let's recap!

The process of compiling code, running tests, and verifying the quality of your software is collectively known as a build.

You can verify the overall quality of your Java projects as part of the build by using plugins for your build tool (E.g., Maven or Gradle)

Generating human readable and visual reports about the health of your codebase lets everyone on your team know how well or badly you are doing. Remember that the whole team is responsible for the quality of your software.

Maven has several useful plugins which gives you confidence in your software and helps report on them:

Plugin | What does this give us? |

Surefire Plugin | Provides XML and HTML reports of JUnit tests. |

Checkstyle | Provides XML and HTML reports of conformance to agreed coding styles. |

Jacoco | Provides HTML and XML TEST COVERAGE reports describing how much of your code is tested. Can be used to fail a build if we don’t have enough tests! |

FindBugs | Performs static analysis by inspecting code for patterns which look like they are introducing bugs. |

Phew! You've already got a lot of testing under your belt. Check what you've learned via the Part 1 quiz, and I'll meet you in the next part to work on more advanced testing techniques!

Test your codebase using advanced unit testing techniques

Label your tests with advanced JUnit annotations

When you’re looking for something in a book, you can usually check the contents page and jump to the right chapter. 📖 If you have to read through every page to find what you need, it either has a bad index or is not structured well. The same is true for your tests. Let's check out some ways to make your tests readable.

Use @Category to label similar tests

JUnit 4 comes with some useful annotations which let you label your tests, a little like marking which chapter or topic they fall under. If someone asked about where to find your tests on say, temperature conversion, you could find all of them quickly by labeling them with the same category name. JUnit4 provides @Category for this very purpose. Every class or method you want to label gets annotated with @Category.

Check out this ConversionCalculator test with line numbers on the left:

@Category(Categories.ConversionTests.class)

public class ConversionCalculatorTest {

private ConversionCalculator calculatorUnderTest = new ConversionCalculator();

@Test

@Category({Categories.FahrenheitTests.class, Categories.TemperatureTests.class})

public void celsiusToFahrenheit_returnsAFahrenheitTemperature_whenCelsiusIsZero() {

Double actualFahrenheit = calculatorUnderTest.celsiusToFahrenheit(celsiusTemperature: 0.0)

assertThat(actualFahrenehit, is(equalTo(operand:32.0)));

}

@Test

@Category({Categories.TemperatureTests.class})

public void FahrenheitToCelsius_returnsZerpCelsiusTempurature_whenThirtyTwo() {

Double actualCelsius = calculatorUnderTest.fahrenheitToCelsius(fahrenheitTemperaure:32.0);

assertThat(actualCelsius, is (equalTo(operand:0.0)));

}

@Test

public void litresToGallons_returnsOneGallon_whenConvertingTheEquivalentLitres() {

Double actualLitres = calculatorUnderTest.litresToGallons(litreVolume:3.78541);

assertThat(actualLitres, is(equalTo(operand:1.0)));

}

@Test

public void radiusToAreaOfCircle_returnsPi_whenWeHaveARadiusOfOne() {

Double actualArea = calculatorUnderTest.radiusToAreaOfCircle(1.0);

assertThat(actualArea, is(equalTo(PI)));

}

}Have a look at line 1. All the tests in the ConversionCalculatorTests class have been marked as conversion tests. Line 7 additionally marks one test as a Fahrenheit test. Lines 7 and 14 mark two tests as also being TemperatureTests.

@Category has one slightly annoying restriction: The labels you use should be classes or interfaces. So to label tests as Fahrenheit, you first create an interface which contains all your labels, like below:

public interface Categories {

interface TemperatureTests {}

interface FahrenheitTests {}

interface ConversionTests {}

} Then mark your class or test with Categories.FahrenheitTests.

This is how you run just the FahrenheitTests using Maven:

mvn -Dgroups='com.openclassrooms.testing.Categories$FahrenheitTests' test`

And the results look like this:

Use the @Tag to categorize tests more easily

So far we’re focused on JUnit4 features. JUnit5 has recently been released, and you’re most likely to see both JUnit4 and JUnit5 in the workplace today. As a Java engineer, it will be up to you, and your team, to decide which to use on new projects. A company’s standards can take a while to change, but fortunately, junit-vintage-engine is a dependency which allows you to migrate your JUnit4 tests to Junit5 more easily.

New versions always bring improvements. Take @Tag from JUnit5 for instance. Using @Category to label your tests meant that you had to create an empty interface each time. Well that’s a waste, isn’t it? It only exists to be used in your annotations. @Tag is way better. You think of a label and use it. @Tag(“fahrenheitTest”) would “just work!™” You also get to describe your tests in plain English, so when they fail, you’re not left staring at a test name like CalculatorTests and wondering what it was about the calculator that you wanted to prove!?

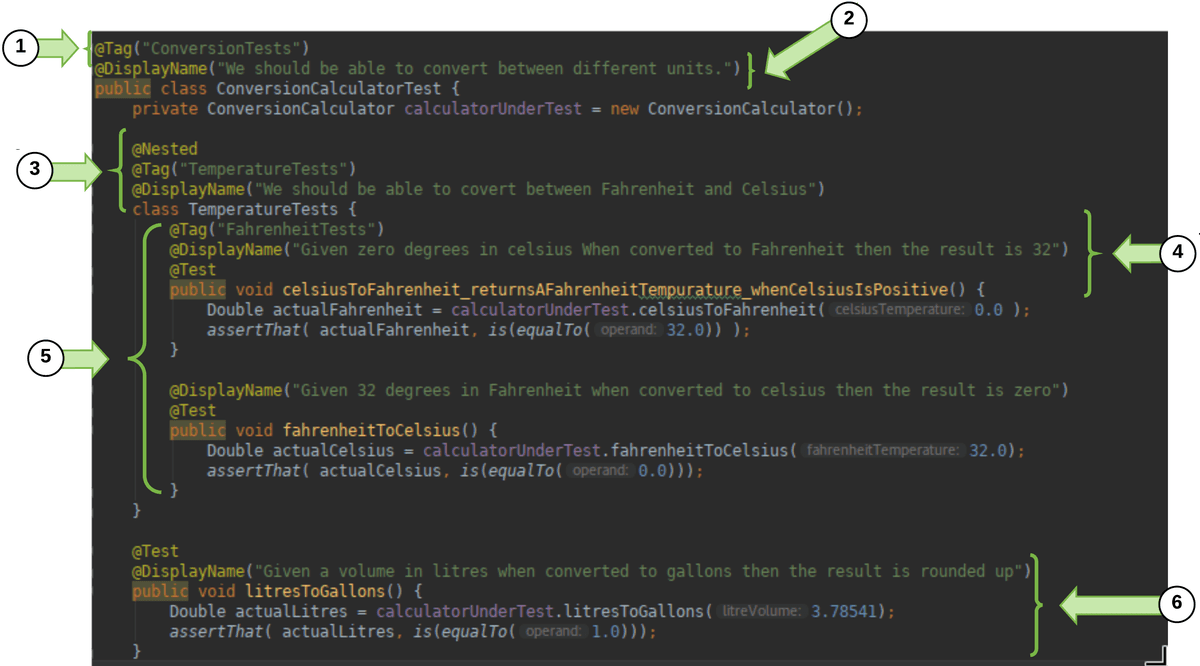

I've highlighted how you can use the @Tag annotation along with two other great annotations: @DisplayName and @Nested. Let's look at the most interesting bits step by step:

( 1 )

@Tagmarks all the tests as ConversionTests.( 2 )

@DisplayNamelets you name your tests so they're readable for anyone.( 3 )

@Nestedlets you group tests in an inner class.

( 4 ) You can add

@Displaynameand@Tagto each@Testand@Nested block.( 5 ) Many tests are grouped into

@Nested. This way one failing test would fail the whole group.( 6 ) Other tests can be separated out (and remain untested).

When that JUnit5 test runs, the results also read more naturally!!

To get started, import the JUnit 5 annotations.

import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Nested;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Tag;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;Try it out for yourself!

Have a look at the code and see if you can TDD a conversion from miles to kilometers. Use the @Tag to tag these tests with distance. Also, use the @DisplayName tags to make the test meaningful in the test report.

Clone the repository below and run Maven commands in its README.md.

git clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJavaC.git

Or use your IDE to clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJavaC.git

Use @RunWith to designate a test runner

@RunWith is how you decide which class runs your test for you and makes your annotations work.

Hold on, doesn't JUnit just do this for me?

Spot on! Yes, it does. Do you remember our first JUnit tests? @Test was all we needed to mark those methods as tests. JUnit4 and later are designed to just work and start reporting on assertions made in methods marked with @Test That's all that's needed to make all those other great annotations, like @Before and @After work too!

But...a special class called BlockJUnit4ClassRunner is used to make your test run and be able to provide reporting information for plugins like Surefire. This type of special class is called a test runner. It's also the reason you can use all those other great annotations we've shown you!

Will JUnit 5's runner know what to do with my JUnit 4 annotations?

Yes. If you work on a project using JUnit 5, you can use its Vintage test engine to support all of JUnit4’s runners. If you're interested in seeing this in practice, check out the JUnit team's examples on GitHub.

So, what can I do with a runner?

Many custom runners exist to help make test writing even easier. All you do is stick an @RunWith(UsefulRunner.class) before your test class. Just replace UsefulRunner with one of the runners you want to use.

You can use custom runners such as Suite.class in JUnit4 to help you use new annotations which better organize or empower your testing. The Suite runner groups a number of test classes so they are associated, and can pass or fail together.

This can be helpful if putting your tests into groups like TemperatureSuite, ArithmeticSuite, etc.

Isn't this similar to @Category and @Tag?

It is! The difference here is that your Suite is a test itself, which reports as having passed or failed. @Category and @Tag are simply about grouping which tests you run.

Let's see this in action:

Many custom runners exist to help make your test writing even easier. All you do is stick an @RunWith(UsefulRunner.class) before your test class. Just replace UsefulRunner with one of the runners you want to use. Here are some examples:

@RunWith(Suite.class)

This lets you group tests into a suite so if one fails, the whole suite fails. Be careful not over complicate your suites!

@RunWith(MockitoJunitRunner.class)

Once you use this runner, you can use the annotation @Mock. @Mock creates a pretend (or mock) ConversionCalculator which our class under tests needs. A mock allows us to focus on testing Calculator by itself. We then set up how it behaves with when and test how it’s used with verify:

@SpringJUnitRunner

The popular Spring framework has its own runner which helps us create mocks of classes which Spring would usually be responsible for creating and destroying. You can read about it here!

@Ignore

Have you ever been working hard on a project, but had someone next to you who just talked and talked and talked? And you couldn’t get anything done because you were so distracted? You might have felt bad, but I bet you wished for a mute button.

I’ve had tests which were like that! Ones which failed and gave me lines and lines of red text, which I had no idea what to do with. Obviously, it’s best to fix the test if you can. However, we live in a world where things need to get delivered to keep our businesses afloat. If the test was badly written or you don’t even know what confidence it’s supposed to be giving you, just tell it to shut up! You can do that with JUnit’s @Ignore.

For example sticking the following annotation before your @Test would stop a test from running and make it clear, why! For example: @Ignore(“Disabled as this fails every Tuesday and it seems to be re-testing unnecessarily”). Make sure you say why you’re ignoring it and promise to come back and fix it later!

Try it out for yourself!

Checkout the JUnit 4 project here. See if you can solve the little challenge in the README!

Let's recap!

We can describe what a test is about using JUnit4’s @Category and JUnit5’s @Tag

@RunWith can be used to point at a custom JUnit runner which gives us more useful annotations.

@Ignore can be used to silence less than helpful tests.

Apply principles for writing good tests

Have you ever had to care for a plant? You may not have a green thumb, but you probably know something about caring for a plant. You know that they need water, but not too much. You know that they need sunlight, and not to put it in your closet. What else? Soil? You’re unlikely to dump a plant with its roots onto your coffee table and expect it to survive. Depending on the plant, you remember and follow certain principles when you need to. These aren’t rules, but rather guidelines.

Software engineering has many great principles to help you avoid silly mistakes and write better code. Two great engineers, Tim Ottinger and Brett Schuchert, who wrote chapters of the book Clean Code, came up with an acronym which described principles they used to teach others how to write great tests: F.I.R.S.T.

Write great tests with the F.I.R.S.T. principles

F is for fast

How fast is fast? You should be aiming for many hundreds or thousands of tests per second. ⚡️Does that sound like a little too much? Not if each unit test only tests one class.

You'll know if your test isn’t fast when you start running it! According to Tim Ottinger, even a quarter of a second is painfully slow. Tests can build up - especially if you have thousands of them! I’ve known test suites which took hours, which makes it not feasible to run them regularly.

Let’s have a look at some real tests and what this looks like in the code:

As you saw, it's important to keep an eye on how long your tests take to run and investigate the outliers. Where you accidentally become dependent on slower dependencies, such as disks, try to abstract them away by using fakes in place of the real thing!

I is for isolated and independent

Have you ever needed to work through a complex problem by breaking it down into small pieces you could work on separately? Sometimes this makes it easier to stay focused and work your way through any issues. One issue = one cause of the problem = one solution. Tests are the same. When they fail, you want to understand why.

The arrange, act and assert principles we talked about earlier in the course, can help you here. Think about what happens if each test arranges its own class under test, and does only one assertion per test. This ensures that your tests are using separate data: you can isolate them from interfering with one another. There is very little overlap at that point, and so your tests remain independent.

As you can see, it’s easy for tests to fail due to no cause of their own when they are linked through a shared dependency. Unlike code, when you’re testing, it can be okay to repeat yourself if it preserves the isolation of your tests.

R is for repeatable

If you write a test which gives you confidence, it should tell you the same thing, no matter how often or where you run it. Sometimes tests become flaky and have to be run several times to make them pass.

Often when a test is not repeatable, it's because of a change made by one test impacting a later one. An example might be that one test writes a file to a local disk and that data gets queried by a second test, which then passes or fails depending on how smoothly the first write went. It might take a day of debugging the second test to realize the underlying problem was the first!

This doesn’t really fill you with much confidence. How can you be sure that this one pass is any more correct than the four previous failures? If you want to make your test repeatable, avoid any two tests leaking into each other. Remember that arrange from above? That’s where you make sure you start your tests with the new classes and data your tests depend on. Using those build tools discussed earlier in the course will ensure that you can build and test your software just as reliably on any environment - meaning your tests won’t fail for that reason!

In testing, these new classes, and the data that tests depend on are known collectively as test fixtures.

Let’s see this in action:

Did you catch the twist at the end? Our tests ran perfectly on Windows, but it was only through running them on another environment that we realized how easy it is to break the repeatability of our tests.

S is for self-validating

This was clearly thought up by a bunch of engineers. 🙂 Hands up if you think you know what self-validating means?

It validates...itself? 🤷🏽♂️

What it means is that running your test leaves it perfectly clear whether it passed or failed. JUnit does this and fails with red, which lets you red-green-refactor. Also, there is no such thing as an acceptable failure; something you hear from time to time. If you can’t rely on a test, it shouldn’t run. That’s what @Ignore is for! 😉

By using a testing framework like JUnit, utilizing assertion libraries, and writing specific tests, you can ensure that if a test fails, there will be clear and unambiguous reporting that tells you exactly what passed or failed.

Let’s see this in action:

T is for thorough and timely

Now, according to Clean Code, T originally stood for timely. The idea was that your tests should be written as close to when you write your code as possible. By writing your test when you write your code, both the code and test can be designed to respect F.I.R.S.T.

In his book Clean Code, Tim Ottinger wrote:

“Testing post-facto requires developers to have the fortitude to refactor working code until they have a battery of tests that fulfill these FIRST principles.”

If you test first, you’re set up to thoroughly test your code, because it’s made for it. So let’s do that in the IDE and let a thorough and timely testing discipline help us build sound and well-tested code:

Today the T is often considered to stand for thorough, meaning that your code is tested extensively for positive and negative cases. Since the best way to write thorough tests is to make sure you’ve written thoroughly testable code, they point to the same outcome.

So...what should I be testing for?

To drive the design of your code through TDDing, and build that base of your testing pyramid, you want to ask some of the following questions:

Have I got a happy path test for each scenario I’ve coded?

Have I thought about negative paths for these scenarios? What if a vampire’s date of birth was after his death, due to resurrection? Could my system cope with this? Assuming you work in Transylvania? 🦇

Does each exception I throw get tested?

Is there a scenario where I don’t change the type of data I’m testing with, but can cause it to do something unexpected? What if I pass it a null or an empty string?

Did I remember security first? Sadly, it always comes as the last item on the list. Can this code only be run by the users who should run it? What if it’s not?

Asking such questions, and combining your tests with the other tiers of the pyramid can give you the confidence that you’ve been as thorough as possible.

Remember that principles are there to guide you. As you make choices in your software design, you can lean on them to remind you of what you should be considering. In the end, the choice is up to you.

Good tests keep on giving, and a bad test becomes something you can’t really trust. This defeats their purpose. If you follow the F.I.R.S.T. acronym, you’re all set to score yourself a strong foundation on the testing pyramid.

Try it out for yourself!

Now that you've seen examples of the F.I.R.S.T. principles, have a look at the tests and try running them yourself:

git clone https://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJava.git git checkout p2-c2-1-to-5

Or use your IDE to clone httphttps://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJava.gits://github.com/OpenClassrooms-Student-Center/AchieveQualityThroughTestingInJava.git and look at the branch p2-c2-1-to-5. Check out the README.md and see if you can add a test case for the division of two double values.

You can now explore the examples from the screencast and try running the tests with:

mvn test

Naming your unit tests

Naming conventions go hand in hand with F.I.R.S.T. and are incredibly important for building readable code. How do you decide what you’re going to call your unit tests? The class name is easy; you typically group tests by the CUT, so the test class and class are named for one another. For example, MyClassTest would test MyClass. Easy, right? What about the method names?

For a long time, developers (particularly Java developers) had a horrible habit of following this same convention when writing unit tests. What does the method testAdd() tell you about the test? Well, you know it tests add, but is this a happy or sad path assertion? Am I testing negative numbers, positive numbers, or just checking that the method exists? More importantly, does it prove the test cases I’ve been working towards? I can’t tell by the name of the test, and so I definitely won’t be any wiser if it fails!

Developers have come up with a number of naming conventions for tests. Java typically uses camel case, which is a mixture of upperCaseAndLowerCaseLettersWithoutSpaces. However, when you’re writing tests, your goal is to communicate with people, and have test results you can talk about in the real world. Therefore, this rule usually falls by the wayside. Below are a few styles which exist to make tests clearer. For each method name construction style, you can see the important components which should go into creating your method names:

MethodName_StateUnderTest_ExpectedBehavior

Example: add_twoPositiveIntegers_returnsTheirSum()

Variant: Add_TwoPositiveIntegers_ReturnsTheirSum()

Note: This is not camel case, so the question of whether to start each new chunk with a capital is up to you.

MethodName_ExpectedBehavior_StateUnderTest

Example: add_returnsTheSum_ofTwoPositiveIntegers()

Variant: Add_ReturnsTheSum_OfTwoPositiveIntegers()

itShouldExpectedBehaviorConnectingWordStateUnderTest

Example: itShouldCalculateTheSumOfTwoPositiveIntegers()

Variant: testItCalcultesTheSumof..

givenStateUnderTest_whenMethodAction_thenExpectedBehavior

Example: givenTwoPostiveIntegers_whenAdded_thenTheyShouldBeSummed

Variant: givenTwoPositiveIntegerWhenAddedThenTheyShouldBeSummed()

You’re free to mix it up as long as you are consistent, and have proved that your reason for change gives everyone who reads your tests greater clarity.

Remember, these are just a few of many styles you’ll see out there! While the styles in rows three and four read more naturally, in my opinion, the first two are great when you’re building a strong test base and want to be sure that you’ve thoroughly tested each method. This is because the first argument is the method name, and the second is forcing you to consider all the different types of input you may encounter. The example above, for instance, focuses on two positive integers. What about having one negative, or one null? Writing your tests can then help drive the situations your code for.

The underlying goal across all the naming styles is to ensure you clearly communicate what you’re testing. You’ve already seen that JUnit5 lets you use the @DisplayName attribute to better name your tests. This complements a good method name, and allows you to make sure you clearly communicate what you’re testing. Whatever you pick, or find in a project, remember to be consistent.

Let's recap!

Make sure your tests have names that clearly describe what they are testing. Pick a style and stick to it!

Use the F.I.R.S.T. principles to keep your tests:

PRINCIPLE | What does this mean? |

Fast | Even half a second is too slow. You need thousands of tests to run in less than a few seconds. |

Isolated and independent | When a test fails, you want to know what has failed. Test one thing at a time and only use more than one assertion if you must. |

Repeatable | You can’t trust tests which sometimes fail or sometimes pass. You need to build tests which avoid interfering with one another and are self-sufficient enough to always give the same result. |

Self-validating | Use the available assertion libraries, write specific tests, and let your testing framework take care of everything else. You can trust it to run and present clear reports on your tests. |

Timely and thorough | Use TDD and write your tests as you write your code. Explore the full breadth of things your method could do and write lots of unit tests. |

Improve class design by protecting against the unexpected

Have you ever been certain about a particular restaurant’s opening hours? You’ve been there a million times. Then one holiday you're hungry and want to eat there, but you suddenly realize that you don't know if they're open or not! 😦 What do you do? You ask Google!

Writing a test for situations which are outside of the ordinary is a little like asking the great oracle of Google. You get to define and prove how your software would respond to those irregular situations. By doing so, you get to avoid the pain of being surprised by unexpected failures in real life! Remember the Ariane rocket unexpectedly turning to its engineers yelling, “surprise!” in the first chapter? 😛

Up until now, we’ve only covered the more intuitive and obvious sad paths like trying to add a null to a number. You want to have great unit tests, right? This involves considering a range of unusual situations in which your app might be used and testing for them. How do you come up with these? Fortunately, testers before us have thought about this, and there are several different types of unexpected scenarios you should consider when writing tests. Let’s dive in!

Leverage edge cases for sad paths

Edge cases are test cases designed to handle the unexpected at the edge of your system and data limits.

What’s the edge of your system? And why are we talking about data limits?

This happens when the data you're working with pushes your code to the extremes of either your business rules or Java’s own types. Let's take each of these in turn.

Edge cases from business rules

First, consider working in a company which streamed music to people over the internet. To listen to music without the annoying interruption of commercials, your users might need to have a paid subscription for that month. What happens when a listener starts playing a two-minute song, one minute before their subscription expires? Perhaps they have a quota of how many songs they can listen to at a time; what happens if two songs are started almost simultaneously - will they listen to both? Such rules define limits of how your software is used, based on the needs of your business.

Edge cases from technical and physical limits

The biggest positive number an integer can hold is about 2,147,483,647. This special number is stored in Integer.MAX_VALUE. If you were building a calculator, what do you think would happen if you added 1 to this? 1 more than the maximum? This type of edge case is a boundary condition.

Simply adding 1 to a large number can counter-intuitively result in a very small negative number. Don't believe me? Let's prove it!

To see what Java thinks about it, use jshell. Here’s an example of what you’d see. The value on the second row after the ‘⇒’ is the answer to Integer.MAX_VALUE +1.

Wow! That is a really small negative number! I only added one! How should your calculator deal with this? There's a new question to ask your product owner!

When you’re having fun with puzzles, the last thing you want is for this situation to stump your users. You might want to avoid this sort of error by throwing an exception if either argument is more than half of MAX_VALUE. Or, you might choose to use different data type, such as a long. Before deciding on what to do, you need to recognize that the edge case exists.

How can I find good edge cases to test for?

Good questions to ask when looking for edge cases are:

What would be a wacky value to pass to this method, which is still legally allowed by its defined type? E.g., Passing a null, empty or insanely long string to Interger.parseInt(String)

Will my app be working in a few years? Do my business rules allow for increasing volumes of data (e.g., larger collections)? Do I have counters or strings which will grow to present problems later?

If writing a method, ask the question, "What could I try to do to break it?" Does it take any arguments which I could try to pass with unusual values? Such as nulls, incorrectly configured objects, or empty strings, for instance.

Do I need to code with some level of precision for my test cases (e.g., two decimal place accuracy)? How should my code behave if it has to round several times? For example, divide by two and round;

@Testdivide by two and round again. Would it still be accurate enough?

To help you get your head around these, let's work through an example:

When you start testing your edge cases, remember that if it fails and there’s no solution, figure out a graceful way to deal with the failure. Always consult with your team and product owner. You don’t get to make up what happens by yourself. 🙂

Use corner cases for your sad paths

Have you ever had a really bad day? One of those where everything seems to be going against you? Your train might have been delayed, or perhaps you were stuck in traffic? 🚧 That morning cup of coffee might have fallen out of your hands. ☕️ Even the internet is against you! 📡

Your software has to run in that same real world, which is filled with imperfections, glitches, and best efforts. When you release your code, it will run on a computer of some sort, far away from your desktop. Unexpected things might happen. Engineers sometimes joke that the cloud is only someone else’s computer! (The providers still use a real computer to run their cloud on.) Reaching their computers will depend on global internet infrastructure for connectivity. Your code also depends indirectly on the operating system in which your JVM runs. If you think about it, there are a lot of working parts. Every now and then one will go wrong despite all your best efforts.

You can’t always predict what might go wrong, but there are questions you can ask to help test your code for situations which might affect your ability to keep commitments. Making a bad mistake can affect your company’s reputation and may even affect its revenue! Worse than that, it might affect the day of a real user out in the world.

There are so many possibilities, where do I even start? 😧

Good question! Below are some questions to ask when looking for corner cases. Remember, not all corner cases will make sense to test. You’ll want to identify some and then prioritize which ones need to be handled. Check them out: